William G. deMatteo

William G. deMatteo was born on March 17, 1895 in the tiny fishing village of Acciaroli in the province of Salerno, Italy. His family was comprised entirely of fisherman, including his father, Luciano. His given name was Gaetano. About sixty years later Ernest Hemingway would be inspired by the fishermen of Acciaroli to write “The Old Man and the Sea.”

William G. deMatteo was born on March 17, 1895 in the tiny fishing village of Acciaroli in the province of Salerno, Italy. His family was comprised entirely of fisherman, including his father, Luciano. His given name was Gaetano. About sixty years later Ernest Hemingway would be inspired by the fishermen of Acciaroli to write “The Old Man and the Sea.”

Luciano emigrated to the United States a few years later and became a U.S. citizen. He returned to Italy, collected Gaetano, and brought him to New York in 1905. He was ten years old. The name William was mysteriously added to his immigration papers at Ellis Island and from that day he went by the name William G. deMatteo.

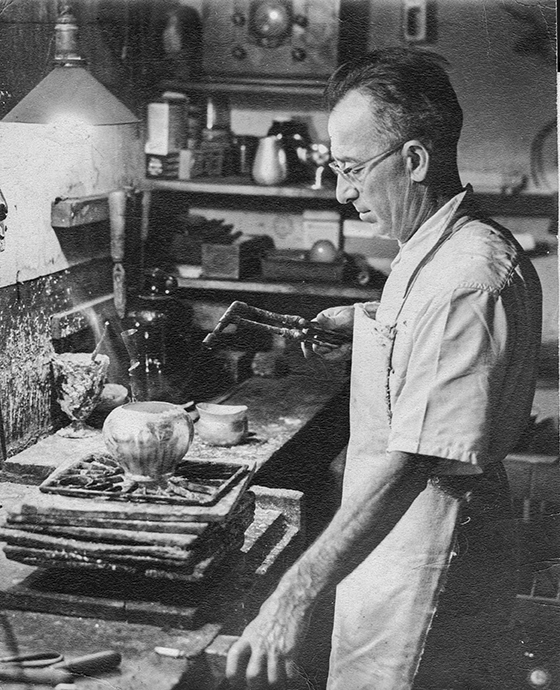

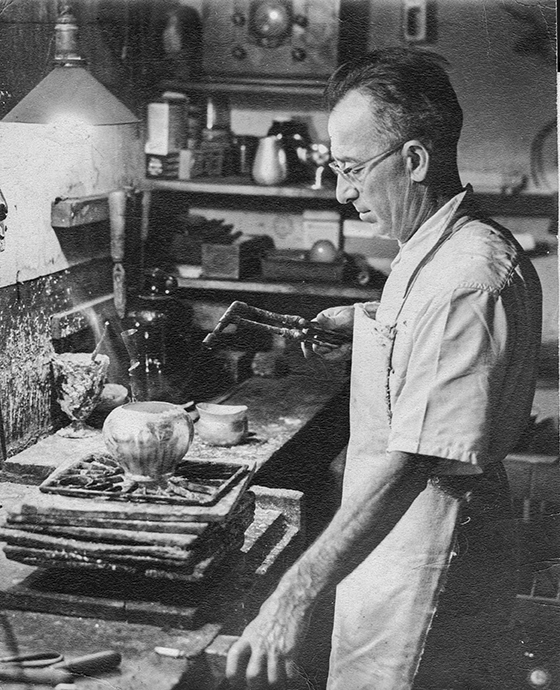

As a boy, he claimed a desire to become a doctor but his formal education ended upon his arrival in America and he was immediately put to work. He held an assortment of menial jobs until one day, at age fourteen, he was hired to sweep floors at Reed & Barton’s Fifth Avenue workshop. Someone there took a liking to him and he was quickly made an apprentice. In five years he was a journeyman silversmith and foreman at the shop, probably the youngest person to hold such a position. During this period, in 1917, he was married. He and his new wife, Elizabeth, were married for sixty-four years.

In 1921, at the advanced age of twenty-six, he opened his own shop in New York City. Little is known about this period and it seems that he supported himself by doing repair work. An anecdote exists about a shady business partner who ran off with the inventory. During this period he and Elizabeth had two children, Margaret, born in 1920 and William, born in 1923. In 1926 he built a small house at 53 Harcourt Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey, a close suburb of New York City. Behind the house was a small shop in which he worked until he retired.

By the time he moved into his new shop, deMatteo had a stable clientele and steady work. He had managed to build a comfortable home for his family by designing and making silver items for the carriage trade in nearby New York City. He was eager to assimilate into the American middle class. He enjoyed buying nice cars. He was an avid gardener and he bought an adjoining building lot for his garden. His garden yielded prize winning dahlias. The wheelbarrow he used in his garden, which he could see from his workshop window, inspied him to make a silver replica, a perfect reproduction in miniature, which he later donated to the Newark Museum.

DeMatteo’s customer list was comprised of the elite of Manhattan’s finest retailers, at least those that dealt in silver holloware. In the early years, he took commissions making specific pieces requested by his customers. Many of these were reproductions for S. Wyler, and Shrubsole.

A few years later, the depression dampened New York’s economy and, naturally, deMatteo’s business slumped as a result. Luckily, he was well established by then and his business had low overhead. In fact, he suffered far less that many of his friends and neighbors who had worked in business in New York and were now unemployed.

He had employed, off and on, a string of helpers in the shop, none of which lasted. During the early years of the depression there was less need for help and as business picked up in the thirties, he invoked a secret weapon.

His son, Bill, who had been born in 1923, was now old enough to work in the shop. DeMatteo built a wooden box for him to stand on and set out to teach him all he could about the trade. As his new helper grew, business improved and the extra pair of hands was needed. By this time, deMatteo was producing commissioned special orders for his customers, primarily Tiffany and Cartier. On the floor of deMatteo’s shop he painted a line which was a measured distance from a shelf on the wall. The line represented the distance from the curb to the window at Tiffany on Fifth Avenue. He would inspect every piece at this distance to see the pieces balance and flow. When he was satisfied he declared the item, “O.K. from Fifth Avenue.” Business was steady and life was good for the deMatteo family. As a teenager, Bill improved his skills until he was a fully qualified silversmith in his own right.

Bill was interested in other things and he joined the Navy during World War II to fulfill his desire to fly. Losing his captive helper was probably difficult for the elder deMatteo and the shop was very busy.

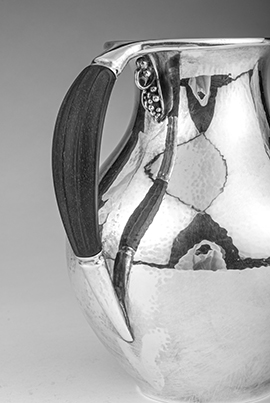

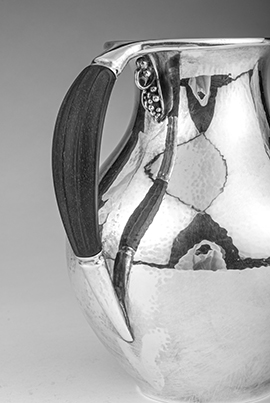

During this period, Frederik Lunning began commissioning deMatteo to make pieces in the style of Georg Jensen in order that he could sell them in his Georg Jensen USA stores during the War. deMatteo took to these designs immediately and had an affinity for the style. The designs were not exact copies of Jensen pieces but were close enough that an ordinary consumer might not detect a difference. Lunning also used Alphonse LaPaglia for this purpose and deMatteo’s and LaPaglia’s Jensen-style pieces provide an interesting addition for Jensen silver collectors. The quality of the design and workmanship is equal to the Danish products and they are rarer, more varied and slightly idiosyncratic. For years, the “mystery” behind the deMatteo and LaPaglia silver fostered a sinister reputation that is undeserved since the silver of both makers is lovely and highly collectable.

DeMatteo made thousands of pieces in a few hundred designs in the Jensen style for sale at Lunning’s store and catalog. He continued to make these and similar designs until he retired and they represent his best known work. As late as 1974, there was still a deMatteo fluted compote for sale in the Manhattan store.

DeMatteo’s take on Jensen’s number 264 compote provides an interesting insight into his methods and a contrast with the George Jensen factory operation. His compote number 69 was made in at least a dozen variations, probably many more. All of them share the same seven inch flared bowl, approximately two inches deep. They are all seven inches tall. Most of them have a similar 3 ½ inch base. The base and bowl were hand-raised and planished in small batches, usually from gauge 18 stock. The cross-section of the bases varies, the curve of which needed to match the width of the bottom of the stem which often varied in dimension. Most of the compotes had beaded wire trimming the bottom and top of the base where it meets the stem, some did not and still others had various round gallery, sometimes with a detail turned in on the lathe. The compote stems varied considerably. Generally, it is a tapered cone about three inches tall, about ½ inch wide at the bottom and about an inch wide at the top. Most were helically fluted, similar to Jensen’s, but some had double twists, some had vertical flutes and many were plain with no fluting at all. There is a small “spacer” bowl between the bowl and the stem. It is a shallow cup with scallops filed out and is the structure that holds the grape vines and clusters. The grape clusters offered scope for deMatteo to vary virtually every piece. The number of clusters and their size varies widely.

Occasionally, he made this piece with lily bud castings in place of grapes and naturally he made some naked examples with no grapes at all. The number 69 compote was a staple at deMatteo’s shop and he made them for decades, often a dozen or more at one time. It is a good example of deMatteo taking inspiration from an existing and popular Jensen design for sale by Lunning in America.

The Jensen-inspired items in deMatteo’s design book run the gamut from nearly identical reproductions of Jensen designs as in his number 46 tea and coffee service, which is almost indistinguishable from Jensen’s famous number 2 service to wholly original designs in the Jensen style. A good example of the latter is his number 251 oval centerpiece. No real corrolary exists in the Jensen catalog for this piece but it is unmistakably Jensenesque. It proved so popular that Jensen’s New York store continued to sell it long after the War, featuring it in their advertising and displaying it in their window.

The popularity of the style declined for a while and deMatteo supplemented them with early American reproductions that he was commissioned to make by his son Bill, who by now was the Master Silversmith at Colonial Williamsburg. By now deMatteo spent his winters in Florida and spent a few busman’s holiday weeks a year in Bill’s Williamsburg shop.

The term hand-made is often misused or exaggerated in modern parlance but it was absolutely accurate applied to deMatteo’s methods. His small and modest shop contained very little machinery. The two most important skills a silversmith brings to bear in making these kinds of items, soldering and hammering are not easily mechanized. He was not a large man and he was probably even smaller as a boy when he learned to raise and planish at Reed & Barton. He was taught to hammer as most silversmiths do, towards their body but found because of his size, that there was more mechanical advantage hammering away from his body, like a carpenter driving a nail. He used this “backwards” technique his whole life and, naturally, passed it on to his son. For decades, the silversmiths taught at Colonial Williamsburg were oddities because they all hammered backwards.

Eventually, the rigors of hand fabrication lost their appeal and so in 1968 he retired to Florida for good and turned over some silver pieces and tools to his family, much of which is photographed here. His retirement lasted unti his death in 1981. The photos show his attention to detail and his overall sense of balance, so that it’s easy to see why his work was “O.K. from Fifth Avenue.”

William G. deMatteo was born on March 17, 1895 in the tiny fishing village of Acciaroli in the province of Salerno, Italy. His family was comprised entirely of fisherman, including his father, Luciano. His given name was Gaetano. About sixty years later Ernest Hemingway would be inspired by the fishermen of Acciaroli to write “The Old Man and the Sea.”

William G. deMatteo was born on March 17, 1895 in the tiny fishing village of Acciaroli in the province of Salerno, Italy. His family was comprised entirely of fisherman, including his father, Luciano. His given name was Gaetano. About sixty years later Ernest Hemingway would be inspired by the fishermen of Acciaroli to write “The Old Man and the Sea.”